x

Warka’s Jewish Community

The first records of Jewish settlement in Mazovia date back to the 14th century. The intensive development of trade, advances in craft specialization, and religious tolerance that marked the 15th and 16th centuries spurred Jewish communities. However, the war against Sweden in the middle of the 17th century hindered trade. In order to revive it, Jewish merchants and craftsmen were allowed to settle in Grójec and its neighboring towns.

Jews gradually began to control trade and partially also artisanship. Nonetheless, the Jewish population grew slowly in the 18th century. A new law promulgated in 1768 that lifted the overall ban regarding Jewish settlements in towns and cities caused an influx of the Jewish population. The years 1795–1809 marked an accelerated development of trade and craft, which again led to a significant increase in the number of the Jewish population in the towns of the District of Grójec, including Warka.

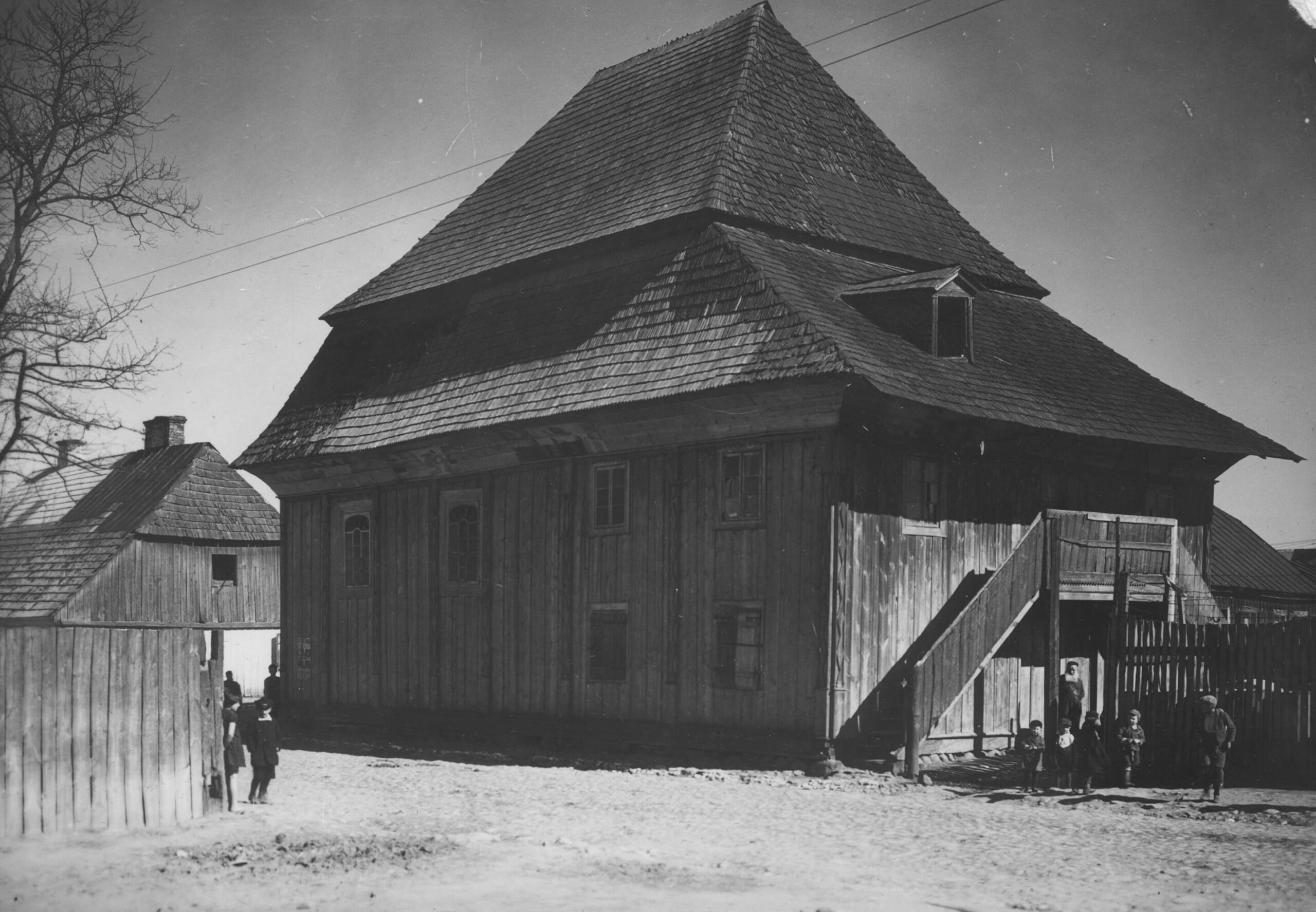

The first significant Jewish town communities were established in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (Grójec, Mogielnica, Warka, Tarczyn). Jewish houses were mainly located on a handful of streets, featuring a synagogue, cheder (a type of school), mikveh (a pool of natural water for ritual baths), and a suburban cemetery.

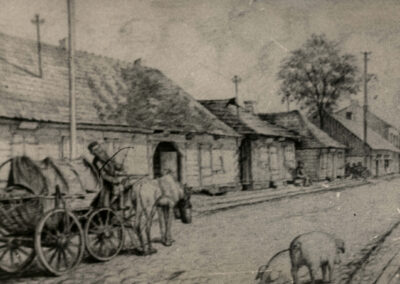

Warka was not much different. Jews lived at Długa, Warszawska, Jatkowa, Rynek, and Senatorska Streets. They had their own synagogue, a bathhouse, and a prayer house. The Jewish cemetery was located on a hill on the Pilica River, west of today’s Baczyńskiego Street.

The hardships that shrouded the beginning of the 19th century gave rise to a Hasidic movement in Warka, which offered “spiritual strength and joy,” shaped beliefs, comforted the tormented and oppressed. It created a vision of an afterlife in freedom and wealth.

In Warka, this movement was represented by an outstanding leader–tzaddik Izaak Kalisz (1779–1848), who founded a Hasidic dynasty in Warka, which was continued by his sons, including Menachem Mendel (1819–1868), known as the ‘Silent Tzaddik.‘

In Warka, Jews worked mainly in trade, which they dominated in 1823–1830, when a unit called ‘the racketeers’ stationed in Town. According to W.H. Gawarecki, the number of Jews in 1826 constituted 920 individuals among the total town population of 1,871. In 1844, the number of Warka residents rose to 2,557, and the number of Jews to 1,398. After the January Uprising, in 1865, among 3,172 people living in Warka, there were 2,081 Jews.

In the late 19th century began the “national and cultural assimilation of particular groups of the bourgeoisie, the Jewish intelligentsia, and the Jewish poor.” Its effects could be seen at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Many Jews joined the ranks of the Polish intelligentsia and began to participate in political life.

In the years 1915–1918, a certain Wersmsing, allegedly of Jewish descent, was Warka Mayor, and in 1921, 7 out of 15 town councilors were Jewish. In the 1930s, Jews were doctors, feldshers, and restaurateurs, but also watchmakers, tailors, shoemakers, confectioners, and bakers.

Rich Jewish merchants and craftsmen held high political positions, i.e. they were members of the Mayor’s Council of Advisors and Town Council board members. However, the majority of Jews was much poorer: they engaged in petty trade, owned market stands, etc. Before the outbreak of World War II, in 1938, there were 2,173 Jews in Warka. They constituted 38.8 percent of the Town’s population. The Jews occupied only 75 out of the 451 houses in Warka. Therefore, it can be said that they lived in high density.

World War II came to signify the extermination of the Jewish population. As early as in the first months of the war, Jews got to experience the bestiality of the German occupant. Robbery and destruction of Jewish stores and all their belongings was ongoing. Later, workshops belonging to shoemakers, tailors, saddlers, hat makers, bakers, etc. were confiscated and handed over to Germans and Volksdeutsche. Religious feelings were being insulted e.g. by shaving or singeing beards. The Germans burned down the wooden synagogue and with it, many valuable fabrics that were used as decorations.

Extensive looting and property extortion were carried out during Jadwiga Kosmahl’s time in office as Warka Mayor. In November 1939, Jews were obliged to wear armbands with the Star of David and to establish 12-person Jewish Councils, whose composition was decided by district governors and mayors. The Judenrats consisted of the wealthiest Jews, who were forced to carry out all the German demands.

The order to establish ghettos in Jewish population centers came at around the same time. The ghetto in Warka was created along the Mostowa, Farna, Rynek, and Długa Streets. On February 21, 1941, over 2,000 Jewish people constituting almost the entire Warka’s Jewish population were forced to leave the ghetto with nothing but a carry-on and proceed to the train station, from where they were transported to the ghetto in Warsaw (with some of them being transported to different concentration camps.)

Despite the inherent danger, Poles continued to help Jews. We know of several Warka families who hid Jews, including children, e.g. the Dąmbski family that owned the property in Winiary. Unfortunately, sources do not say how many of the Warka Jews survived the war. According to the “Chronicle of the Town of Warka” (“Kronika Miasta Warki”) by W. Krawczyk, about 200 Jews were saved.